⚔️ Putin's Russia in the Long Now

What moves Putin & Co? Why do they do what they do? And how do they see the world?

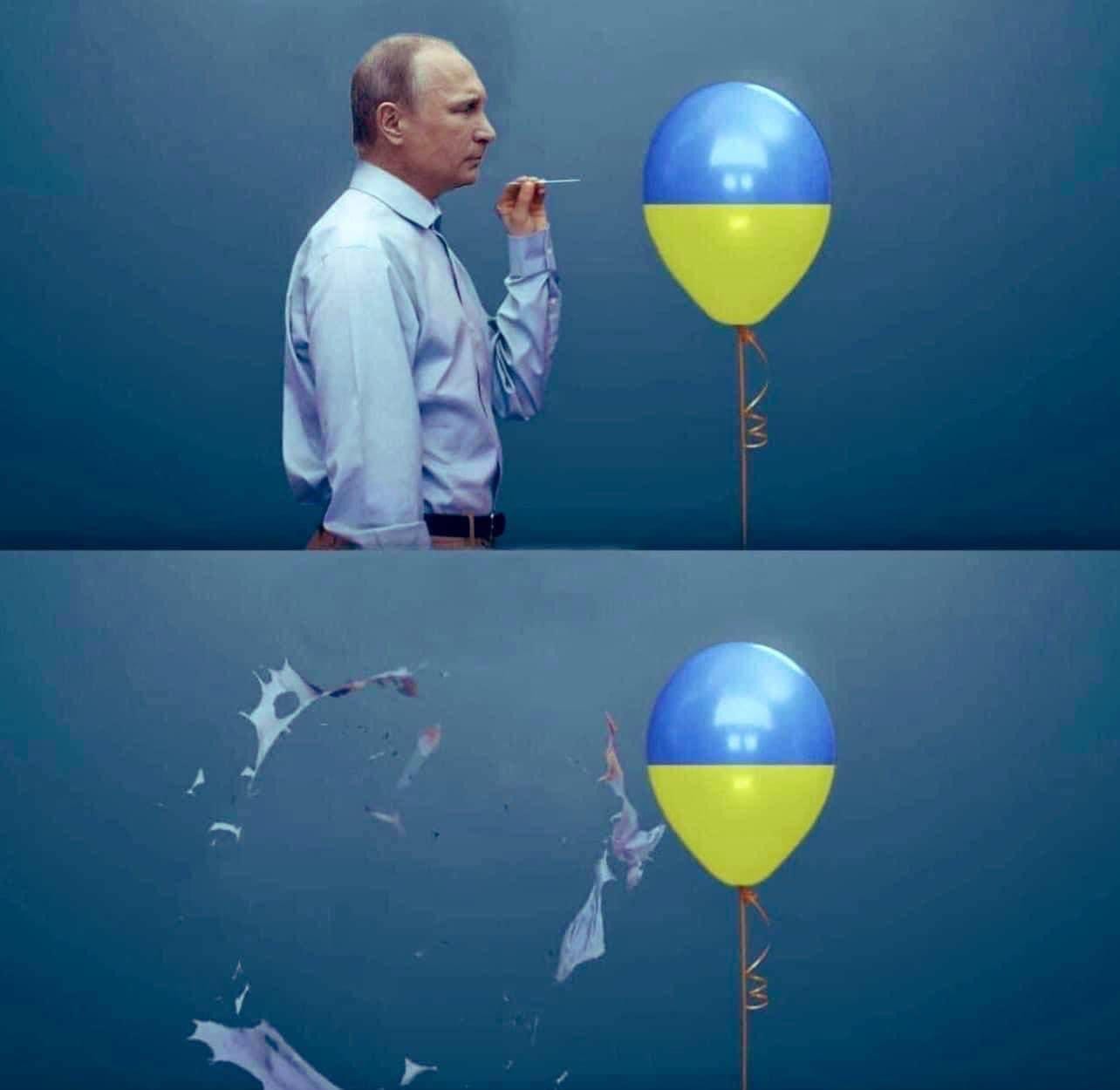

Putin and his cronies are cornered, lashing out with nuclear threats and losing grip on a war they thought they could easily win. In light of a looming nuclear escalation, a question that rose at the beginning of the Russo-Ukraine war, rises again: Can Putin be considered a rational actor? And if so, what kind of rationale does he adhere to? What motivates him? What values does he operate by?

In the Western media, we have seen three dominant narratives surfacing that attempt to provide context for Putin's actions. Super briefly, these are the narratives we now see recurring, often overlapping, over and over again:

As a KGB man traumatised by the Fall of the Wall, Putin sees democratization - manifested in NATO and EU expansion and cultural Westernisation - in Russia's periphery and in Russia's traditional sphere of influence as a major threat. Incidentally, he has so far managed to contain emerging democratization movements quite effectively.

Putin is fascinated by the idea of Russkiy Mir, the Russian cultural world, and wants to make the old empire a force of significance again in global geopolitics. This vision is rooted in historical thinking. In this vision, the future as an Imperial Empire leans on a strong military force, a large Eurasian territory, centralised decision-making and the Orthodox Church.

Putin isolated himself in an echo chamber of like-minded KGB buddies during the Covid pandemic. As a result, he underestimated the West's response and overestimated the strength of his own military. Because he has backed himself into a corner, he will continue to escalate until he can achieve a compromise that is honourable to himself.

All three are valuable lenses on Putin and Putin's Russia. All three are well-reasoned. (For more extensive expositions of the three narratives described above, read this interview with Viola Hill, this opinion piece by Jane Burbank, listen to this podcast with Timothy Snyder or read this piece in the Correspondent on how gay rights have become symbolic of cultural Westernisation.

Putin as Lord Voldemort, by Kawu, in Wilda, Poznan in Poland. A little further down the street is Volodymyr Zelensky as Harry Potter. The comparison rings truer then we are initially inclined to think. In Harry Potter and the Sorcerer' s Stone, Voldemort says the following: "There is no good and evil, there is only power and those too weak to seek it” We will see in a moment that this view is not far from Putin's cultural mindset. And also that such a cultural mindset is not historically unusual.

The problem with the above narratives is that they are culturally superficial. They do not explain why someone like Putin can attract so much power to himself at all. Or, in other words, what does the concentration of political and economic power with a small group of oligarchs say about Russian society? How is power understood, experienced and exercised in Russia?

And related to this question: the three narratives do not explain the indifference that Putin & Co show toward human suffering. For that is perhaps the greatest mystery to a Western audience. Not only the fate of people in Ukraine, but also the dramatic consequences of economic isolation and military mobilisation for ordinary Russians seem to leave Putin & Co stone cold. What does this cruelty and indifference say about Putin and Putin's Russia?

When we step back, zoom out, and look at Putin's Russia through the lens of the Long Now, we see the outlines of a deeper cultural context. A context that not only marks Putin's thinking and actions, but also tells us much about how power works in Russia today. And it also explains, in part, why the West has so much trouble assessing Putin and predicting his behaviour.

Putin was, in retrospect, pretty clear about his ambitions, his concerns and his objections. He wrote about it, he spoke about it and he talked about it with Western politicians. Putin's worldview is just so far removed from the reality of most Western politicians that they simply didn't hear his warnings and his arguments, or didn't take them seriously.

After Putin's annexation of Crimea in 02014, Angela Merkel (who speaks Russian) said in a phone conversation with Obama that she was not entirely sure Putin was in touch with reality. He lives "in another world," she is reported to have told Obama.

The question is: in what world? (And why, seven years later, are we still not sure?)

Three Historic-Futuristic Cultural Archetypes

In our futurology practice (Studio Monnik) we work with a historic-futuristic taxonomy of societal change; a conceptual toolbox with which we interpret cultural and technological developments and create future scenarios.

With said conceptual framework, we interpret the development of Western modernity, what preceded it and what may follow it. One way we can use this framework is to divide Western history into three cultural-historic archetypes: the Homo Nobilis, the Homo Economicus and the Homo Romanticus.

The Homo Nobilis, Economicus and Romanticus are three cultural archetypes rooted in the information technology of their respective era’s.

The cultural archetypes describe how the speed and reliability of information determines (1) the dominant worldview in a given time or social context, (2) the degree of social trust, (3) the complexity that social institutions can handle, and (4) the social challenges that in turn determine one's social status.

Of course, these archetypes are not historical truths. They are lenses through which we can (somewhat Eurocentrically) interpret the Long Now. Of course, the archetypes are not mutually exclusive; all three archetypes are present in a given time or context, but usually one of the archetypes is dominant.

That said, if we look at Putin and Putin's Russia through the lens of the archetypes, we see an interesting picture of Russian society emerging - a cultural context in which the oligarchy is embedded, from which Putin & Co operate and in which their actions are understandable.

But before we move on to a profile of Putin and Putin's Russia, it is useful to introduce the three cultural archetypes somewhat more extensively.

🛡 The World of the Homo Nobilis

Until the end of the Middle Ages, the dominant information technology was the spoken word. Therefore, trust was a personal matter. One had to first meet someone, speak to them, perhaps even physically touch them, in order to trust them. Everything in this world revolved around personal ties. Friendship and family were important, and people, in the absence of reliable information, surrendered to fate (or the will of God).

In this world, where trust was personal, personal qualities were important. Everything revolved around honesty, courage, trust in God and, above all, loyalty to your chief and tribe. These things determined your trustworthiness and reputation. This was the hyper-subjective world of the Homo Nobilis; a world in which shaking someone's hand was a token of trust and intimacy and "an honest man’s word is his bond” was much more than a quirky expression.

Because information was determined by the spoken word, the flow of information on which people based their actions was irregular and of low quality. And because the quality and quantity of information determines how much complexity a society can handle, it was impossible at the time to build layered social institutions. Something like a rule of law - a set of institutions working together to ensure physical security and justice based on objective rules - was virtually impossible in the world of the spoken word.

Physical security was thus the greatest challenge in the world of Homo Nobilis, making individual physical qualities important. Those who could guarantee physical security were therefore given the most social status. This translated into all kinds of martial norms and values. For Homo Nobilis, war was a natural pastime. Peace - often seasonal - was merely a respite to regain strength.

Power structures were thus very personal in the world of Homo Nobilis. Based, on the one hand, on personal trust and family ties and, on the other, on imposing one's will on others. The latter was done through violence or the threat of violence. Power structures were thus very fragile, because they were very personal; think, for example, of feudalism or mafia organisations.

Thus, in the world of Homo Nobilis, the right of the strongest applied. The one with the will and power to create order out of chaos was the leader chosen by God (or nature). It is the logic of the Strong Man; the autocrat who, along with a few loyal vassals and trusted brothers-in-arms, imposes his will on the land. His will makes law, which makes the "law" subjective, arbitrary and dependent on one's character or mind. Legal certainty, the rule of law, was an unfamiliar concept.

The Homo Nobilis believed above all else in strength (or power) and in the manifestation of strength. This is also what glory means: the visible or palpable manifestation of pure power. Power that the Homo Nobilis experiences as intrinsically subjective. Something emanating from humans or from divine beings. Even forces of nature were subjective manifestations in his perception. Proceeding from the will of God. In other words, the Homo Nobilis lives in a deeply subjective reality.

General Patton, the famous World War II hacking genius, said that war was "the most magnificent rivalry in which man can participate. War brings out the best; it removes all that does not matter.' Violence as a mystical instrument through which man can draw near to himself. He died in 01945.

Because information was based on the spoken word and reliance on personal relationships and because justice was subjective, the Homo Nobilis is inherently dominant in low-trust societies. At the same time, because of his subjective assertiveness and penchant for violence, the Homo Nobilis creates cultural contexts the engender low social trust.

The personal sphere of trust was limited in the world of Homo Nobilis. A sense of community emerged if people who could meet physically. Out of sight was literally out of mind. The public sphere, the place where shared norms and values were formed, was limited. It consisted of physical spaces, such as market squares or council chambers. This is where people met and a community emerged. (For a more comprehensive definition of a public sphere and what a healthy public sphere must meet, see our essay Building Trust in the Electric Age)

In the West, Homo Nobilis has been "banished" to crime, sports competition or action movies. In exceptional situations, where the guarantee of physical safety lapses, the Homo Nobilis regains a social role. Read Oleksandr's reflections here.

👔 The World of the Homo Economicus

The dominance of the Homo Nobilis slowly started gave way from 01450 onwards to that of the Homo Economicus, an archetype closely intertwined with Western Modernity. Modernity was made possible primarily by the introduction of a new information technology. Around 01450, Gutenberg invented the printing press, an invention that quickly spread through Europe.

The printing press made information scalable, allowing the atmosphere of trust to gradually grow. A public sphere emerged. And in time, this translated into reliable social institutions that could guarantee physical safety, legal security and law enforcement. All this paved the way for the dominance of Homo Economicus.

Through the art of printing, people learned to rely on the printed word and the symbolic value of printed securities. Books, magazines, manuals, pamphlets, banknotes, stocks, land and sea maps, diplomas and passports - printed paper was valuable for the information it contained, but it also had great symbolic value: it stood for security. The art of printing literally changed everything.

The flow of information was now no longer sporadic but periodic. The distribution of pamphlets, newspapers, books and magazines created a public sphere. An accessible sphere in which more and more knowledge was available. Literacy took off and the public sphere began to transcend the physical and the personal. Whereas before trust was very personal, a one-to-one affair, now indirect trust became possible.

Through reading the same books, newspapers and maps, people experienced community and connection with people that they had never met in person. In the growing public sphere, new opinions were formulated and new humanistic values became commonplace. Larger cultural, political and linguistic communities emerged based on a shared worldview and shared values. Communities that lived in the imagination, rather than in everyday physical experience (think ‘national identity’).

Community and trust became increasingly abstract experiences, propped up by new protocols for truth-telling, such as the scientific method and journalistic ethics. These new protocols deepened trust in the printed word. In this way, today's high-trust society slowly took its shape.

This more abstract sense of community was supported by a variety of new institutions. The scalability of information (and thus trust) allowed society to handle more complexity. All sorts of new bureaucratic institutions emerged that were both more effective and more objective because they transcended personal ties. This, in turn, manifested itself in a new work ethic: professionalism. And in the negative concepts of corruption and nepotism. The idea of professionalism allowed strangers to cooperate with each other because they trusted that they were on the same page.

Through the emerging humanistic culture, these more objective institutions developed into the democratic rule of law - a complex of institutions that could guarantee physical safety, legal security and law enforcement. Because of the dominance of Western countries, after World War II this translated to the United Nations, the Universal Human Rights, the Geneva Convention and other pillars of the international legal order (however arbitrary and difficult to enforce this legal order was), among others.

Social life thus became more objective, less personal, less arbitrary, less based on the manifestation of one's personal strength or power and more based on generally accepted rules. Not only did organisations become more objective, the view of the world and the view of man also became more objective. Man was no longer a divinely inspired and deeply subjective being, but a creature subject to the logic of objective reality. In this context, the Homo Economicus became dominant.

The guarantee of physical security allowed Homo Economicus to start striving for economic security. The emphasis on physical characteristics slowly gave way to an emphasis on possessions. And in a world where economic security is the greatest challenge, it is not the one with the biggest stick that has the most prestige, but the one with the deepest pockets. This emphasis on economic security translated to more and more people, with more and more knowledge, and more and more stuff, in bigger and bigger cities.

The Homo Economicus sees himself as an objective being subject to objective laws of nature. He trusts the printed word and the institutions that guarantee physical security and objective justice. This allows him to focus on economic security. For him, belonging and community are abstract concepts. He lives in cities and feels at home among people he does not know personally, but in whom he recognises himself culturally. He is a systems thinker; for him, the pen is mightier than the sword.

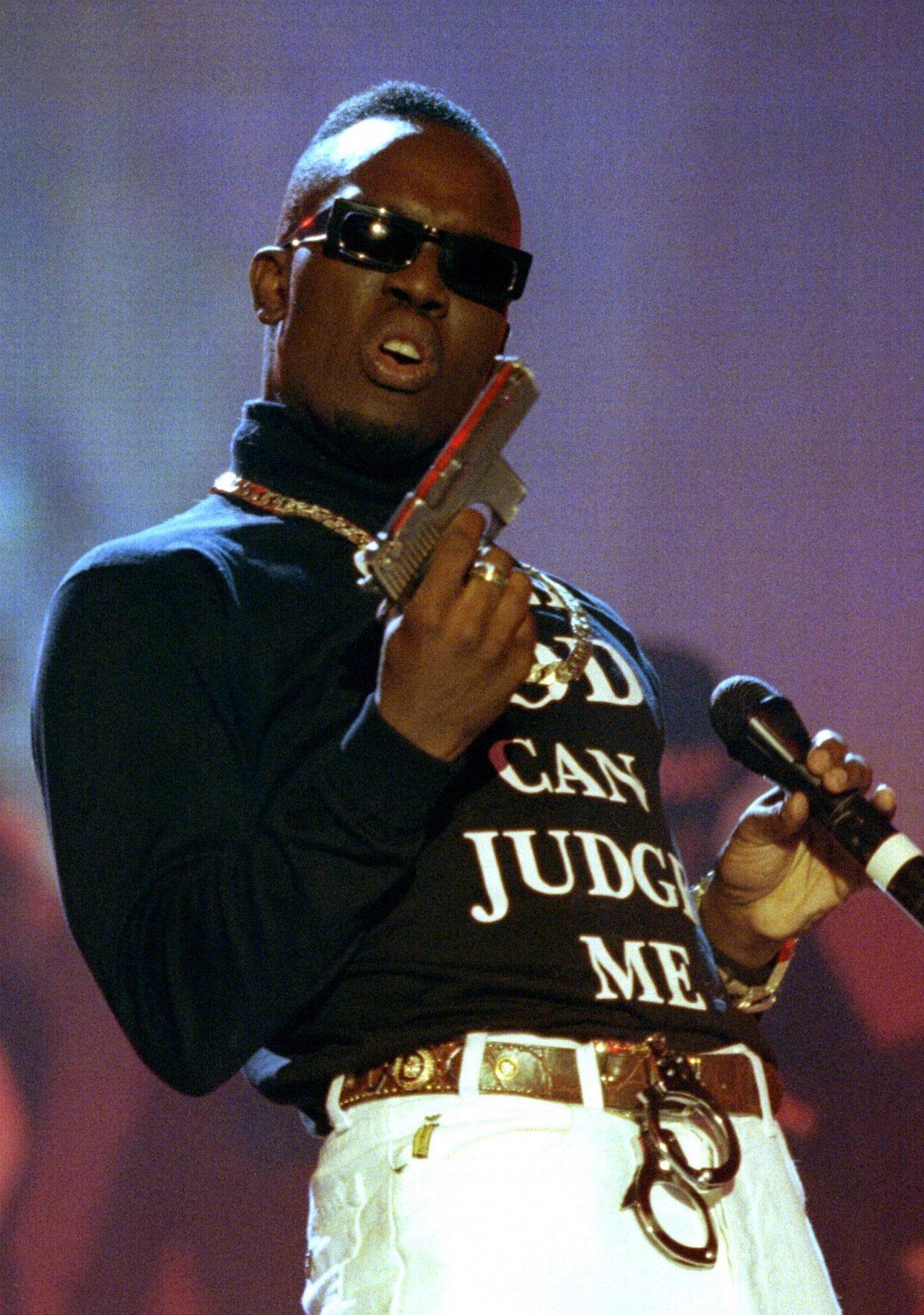

British rapper Mark Morrison performed at the 01997 Brit Awards with lots of bling, a fake gun and a T-shirt that read "Only God Can Judge Me”. Hip-hop is an art movement that emerged from a community in which physical and economic security were not a given, which may explain the display of physical and economic strength. As hip-hop has become part of global culture, both Homo Nobilis and Homo Economicus are experiencing a kind of revival in the popular imagination against the broader cultural context.

💛 The World of the Homo Romanticus

The rise of the humanistic value system, the growing amount of scientific knowledge and the accumulation of wealth translated, step by step, into the cultural, political and economic emancipation of disadvantaged people. More and more people were allowed to participate and share in the wealth that the industrial economy created. Constitutions appeared. Slavery was abolished. School laws, election laws and housing laws came into being. Step by step, the welfare state was constructed. Guaranteed economic security came closer and closer, and this created room, a space, in which the Homo Romanticus could emerge.

The Homo Romanticus is the cultural archetype that, simultaneously with the development of a new information technology - the computer - has the opportunity to shape a new era of trust. We are now in the cultural transition from the world of the Homo Economicus to the world of the Homo Romanticus, the archetype for whom the greatest challenge is not economic security but emotional security.

The Homo Romanticus had been among us for some time, already making its presence felt in the eighteenth century, but it only really surfaced in popular culture with the Beat Generation, the youth and protest movements of the 01960s and the hippies. These movements were carried by young people who grew up in relative abundance. It is the Homo Romanticus' deepest desire to coincide with himself, his community and his natural environment - peace, love and back to the land. But becoming the dominant archetype requires economic security.

Although Homo Economicus is still dominant, Homo Romanticus is close on his heels. The rise of the Homo Romanticus after World War II had not only to do with an abundance mindset, but runs parallel to the development of a new information medium: electronic communication - which led successively to the telegraph, the radio, the television and the computer.

This is Stewart Brand, a hippie prophet from California who, among other things, coined the term "Personal Computer. As well, incidentally, the term The Long Now. The development of the Personal Computer and the WWW was driven by the desire for radical autonomy and is closely linked to the values and norms of the Homo Romanticus.

The World Wide Web and personal computers created a new public sphere, accessible from your desk or smartphone, after which the printed word pretty much faded into a secondary role. Moreover, on the WWW and other Internet apps, information no longer flows periodically but continuously. Also, the direction of flow of information is no longer one-way but two-way.

The printed word is now replaced at lightning speed by the activated word, because that is what computer code is. If the printed word could motivate many people at once to collectively do work, the activated word, in theory, no longer needs people at all to do work - think: artificial intelligence and robotics.

The advent of the activated word thus opens the door to even greater social complexity and, potentially, an even greater deepening of our collective trust. Of course, this is not a certain outcome. We must first provide the commercially centralised and culturally feral web with a renewed architecture of trust (both legal and technological). Just as the scientific method and journalistic ethics gave the printed word an architecture of trust, the activated word must also be founded on a solid and reliable basis of trust.

Much more than the printed public sphere - which was rather top-down, expert-oriented, one-way and static - the digital sphere is bottom-up, spontaneous, interactive and dynamic. Everyone there is sharing personal data and personal information with each other all day long. So this requires an even much more powerful architecture of trust, where truth sources, identities and certificates can be approved, verified and authenticated.

We need an architecture of trust on which to build tomorrow's institutions. So that we can turn our present high-trust society into a super-high-trust society, instead of falling back to a low-trust situation. We are now caught between two public spheres, so to speak - the printed one is already in the bin, but the digital one is still full of bugs. This has created a (temporary) trust crisis in society.

The 01960s were marked by the rise of youth and protest movements. Young people who had grown up in relative abundance suddenly felt the space to critically question the world in which they found themselves. They sought a more authentic connection to themselves, to their communities and to nature. They explicitly rejected the worldview of Homo Economicus. Think of Janis Joplin's song "Mercedez Benz.

The activated word also opens the door to a world in which economic security can be guaranteed, because if robots take over our work, we will either be poor and unemployed or rich and exempt from labor. And this is indeed the other condition for the transition to Homo Romanticus: the guarantee of economic security. We must declare economic security a basic right, just like we did with physical security. Only then can the Homo Romanticus focus fully on the pursuit of emotional security and self-actualisation/self-manifestation.

Thus, a challenge for the Homo Romanticus is to reconcile the subjective world of the Homo Nobilis and the objective world of the Homo Economicus on which the Homo Romanticus depends. Because, the subjective search for emotional belonging - in himself and in the world - can alienate the Homo Romanticus from the objective institutions that guarantee his physical and economic security. Institutions that the Homo Romanticus may perceive as soulless, causing a possible distrust in these institutions, especially now that the public sphere does not yet have a solid trust architecture. The Homo Romanticus is the archetype of the future, but he still has a long way to go (see last week’s edition ‘The Rise of the Homo Romanticus’).

Trump is a classic Homo Nobilis. Wealth for him is a cultural manifestation of his personal glory. (This is more common among heiresses - who seem to think wealth is a physical attribute.) For Trump, family is everything. He recognises no objective institutions, only personal loyalty. His popularity can be explained by (1) the current public sphere not working properly and (2) the subjective Homo Romanticus has a distrust of the objective institutions on which it depends.

Russia as a Hybrid State

The Homo Nobilis, Economicus and Romanticus are cultural archetypes whose historic-futuristic dominance is linked to the information technology prevailing at the time. Moreover, they tell us something about how trust works in a society. In every social context and in every historical era, all three archetypes are present, but usually only one of them is dominant at a time.

We see the successive dominance of the three archetypes especially in Western Modernity. In Northwestern Europe and in the former Anglo-Saxon colonies, such as the United States, Australia and New Zealand, the cultural dominance of the Homo Nobilis was gradually replaced by that of the Homo Economicus. This trend was linked to the industrialisation of the economy, the growing middle class, the emergence of a public sphere through newspapers and magazines, among other things, and the development of the democratic rule of law. In other countries, this development was not at all so chronological.

Russia is an interesting example of this. While the West is in transition from Homo Economicus to Homo Romanticus, Russia is still dominated by the Homo Nobilis, ruling over a hybrid state. A state with institutions that Westerners associate with the world of the Homo Economicus, replete with seemingly objective professionals, but propelled beneath the surface by the subjective money-making urges of a ruling class of oligarchs and their vassals. With Putin at the top, a classic Homo Nobilis.

To further complicate matters, Russia, like many emerging economies, has a thin upper layer of often young knowledge workers who have grown up with Western media and the World Wide Web, and who have often studied or done an internship in Western Europe or the U.S. This layer of the population is at home in the creative and digital economy and, in terms of their worldview, is more in line with the archetype of the Homo Romanticus. It is this layer that has been leaving Russia, en masse since the war started. This creative brain drain is going to affect Russia in the long run.

The hybrid situation of Russian society, in which different cultural archetypes compete with each other, has consequences for how the Russian state functions, for how the average Russian experiences commonality, for how physical security and independent justice are (not) guaranteed, and for what the motives are of those who run the country.

This hybrid situation has historical roots. Until the early twentieth century, Russia was ruled by a tsar who leaned on an aristocratic upper class. By the nineteenth century, a small metropolitan middle class had emerged, but it was dwarfed by Russia's predominantly agrarian population. In Tsarist Russia, the worldview of Homo Nobilis was dominant.

To keep up with the industrial and scientific clout of the West (and later with Japan), the tsar built his own bureaucratic state. This succeeded only sparsely. The bureaucratic institutions of the Russian state had to meet both the objective standards of efficient administration and the subjective motivations of the tsar and the aristocracy. This led to endemic corruption and nepotism.

Russia has always been an oligarchy. It has never known an independent middle class, nor an independent public sphere. Therefore, the objective cultural heritage of the Homo Economicus never became dominant. Everything in Russia served the interests of the Tsar & Co. Even the administration of justice. The guarantee of physical safety and legal security by the state was always under the condition that it was consistent with the private interests of the oligarchy.

This situation continued under the Soviets, then under Yeltsin and then under Putin. Most of today's oligarchs became rich under Yeltsin. In exchange for "protection money" and personal loyalty to Yeltsin, a small number of former Soviet party officials were able to take control of large parts of the Russian economy in the 1990s. But because economic power in a system without legal certainty depends on whoever controls physical power, they remained vassals. They had to do whatever the one with the biggest stick demanded of them. And after Yeltsin, that was Putin.

In the Russia of the Homo Nobilis, where physical safety and legal security are subordinated to the interests of the oligarchy, a broad-based public trust and commonality never developed. In the 1990s, independent media emerged, for the first time, which could have been a harbinger of a mature public sphere. These have all been dismantled or aligned with the interests of the oligarchy in the last two decades.

There is no public sphere in Russia and therefore no public sense of agency - a "togetherness" founded on a general trust that people share the same values, and that can express itself in collective action. Most Russians probably also do not know how a world based on deep social trust functions, or what is expected of them in such a situation. After all, they have never been part of it. Neither has Putin. So the Homo Nobilis is the dominant archetype throughout Russian society. Putin is merely a logical consequence of that.

This is not to say that cultural change is impossible. On the contrary, cultural space may just emerge in which the principles of the Homo Economicus and the Homo Romanticus gain a greater grip on the day-to-day affairs of Russia. But for the foreseeable future, this seems unlikely. The chances of a spontaneous popular uprising against Putin are slim. Only if such a thing were supported by people from the oligarchy would it have a chance of succeeding.

So there is great mutual distrust within Russian society, as well as within the Russian state. Trust is to some extent still based on personal ties and patronage systems. And power arises from one's personal attributes. It almost legitimises itself, making abuse of power a rather hollow accusation. After all, everything in the Russia of the Homo Nobilis is about power - Modern institutions are just a facade of the deeply rooted patronage system.

All this is maintained today by the Homo Nobilis at the top, Putin, who uses intimidation and divide-and-conquer tactics to try to keep things under control, often with a heavy hand.

Such a personal patronage system has disadvantages for the effectiveness of the state. This is evident in how the war in Ukraine is going for Russia now. Indeed, the personal interests of Putin and his oligarch clan stand in the way of effective governance. Things that are important for military strength - well-trained personnel, industrial production, optimal logistics and technological innovation - thrive primarily in a professional domain, the domain of the Homo Economicus. They thrive poorly in a world of intimidation, corruption and bargaining - the world of the Homo Nobilis. That the Russian military functions poorly, therefore, comes as no surprise.

Nor is it any wonder that Putin was unaware of the poor state of his army. In the world of the Homo Nobilis, trust is personal. One places little or no trust in the system. Which well-intentioned official, who aspires to some degree of professionalism, dares to tell "the Czar" that his army is eroded by chronic corruption and nepotism - a situation for which he himself is largely to blame? In Russia, Putin is the emperor without clothes.

Putin as the emperor without clothes. Artwork by Banksy.

Putin as Feudal Lord

So, according to this analysis, Putin and the oligarchy act from the worldview of the Homo Nobilis and Putin relies on rattling state institutions that can only just keep up the appearance of professionalism. Behind a facade of seemingly objective institutions lurks the power structure of the Homo Nobilis.

Putin need not fear a self-aware middle class that might spontaneously revolt. There is none, in the absence of a healthy public sphere and a lack of social trust. All he has to fear is the incompetence of the Russian state and a conspiracy of oligarchs that could manifest itself in a popular uprising or assassination attempt.

That said, the Russian oligarchy can roughly be divided into four categories:

Economic oligarchs, such as Roman Abramovich, who seem to use their capital primarily for the visible manifestation of personal power and international splendor (yachts, jets and sports clubs);

High officials and military who try to provide the civil service and military bureaucracy with some objectivity, professionalism and accountability without, of course, undermining the patronage system of the Homo Nobilis (impossible task and woe betide the one who reveals the emperor's clothes);

Putin's old KGB brothers-in-arms, the so-called "siloviki," who both perpetuate the patronage system and keep the people in place through intimidation, violence, divide-and-conquer and popular demagoguery;

The ring of vassals who rule in Russia's semiautonomous periphery and surrounding countries. Such as Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, Ramzan Kadyrov of Chechnya and the former president of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych, whose fall in 2014 ushered in the Ukraine crisis.

The power structures of the Homo Nobilis were created in a low trust environment and are personal in nature. Each of these oligarchs is thus, directly or indirectly, personally dependent on Putin. Their wealth is often based on mining Russia's natural wealth, "mining" the Russian state, suppressing democratisation movements in Russia's periphery or monopolising a Russian market. And as the fall of Mikhail Khodorkovsky shows, access to these sources of wealth, power and prestige depends on the boss - Putin - and are easily lost.

Alexander Litvinenko was a Russian FSB intelligence officer who accused his superiors of trying to assassinate disgraced oligarch Boris Berezovsky. He fled to England, where he was poisoned with a radioactive substance, a favorite weapon of Putin. A similar fate befell former Russian military man (and double agent) Sergei Skripal and his daughter.

Together, the oligarchs run (or divide) Russia, but they are also divided among themselves into all sorts of factions. It is up to Putin, with the help of his KGB buddies, to keep the factions divided among themselves and dependent on him. As a rule, loyalty is rewarded and disloyalty is ruthlessly punished. Putin must therefore constantly radiate that he is the strongest, the most powerful, because in the world of the Homo Nobilis that is the most important thing. So from time to time, an example must also be set, something that reminds everyone that their lives are in his hand.

So the power structures of the Russian oligarchy work the same as those of a Mafia clan. In a world with no legal security and no guarantee of physical safety, the law of the jungle applies and violence is the ultimate currency. Not surprisingly, according to U.S. intelligence agencies, the Russian oligarchy is closely intertwined with organised crime. The Russian mafia, according to the FBI, operates under the protection of the FSB - Russia's security service. So the Russian mafia leaders are also, directly or indirectly, in a vassal-lender relationship with Putin. Their power also depends on Putin's approval.

Semyon Yudkovich Mogilevich is a Russian mob boss who, according to the FBI, is the boss of the global Russian mafia. His organisation is reportedly under the protection of the Russian security service FSB. He also seems to have established good ties with Putin in the 1990s. There is also a nice photo + theory of the relationship between him and Trump going around. Homo Nobili amongst themselves.

Because Russia has no healthy public sphere and no legal security and independent institutions, there is little public trust. Putin deliberately maintains this so that he can set himself up as a Strong Man who can create order out of chaos through sheer force of will and decisiveness. He also did this after the tumultuous 01990s under Yeltsin. Also to the general public, he must project an image of himself as someone larger than life - a divinely inspired person in whose glory the population feels physically safe and through whom Russia regains prestige.

In a social context where physical security is not guaranteed, the law of the jungle applies. Martial norms, values and imagination are normal in such a context.

In this atmosphere of social distrust and physical insecurity, a raw dynamic of "kicking down and licking up" is not uncommon. There is a culture of imposition of will and humiliation. This does not make large Russian organisations, like the military, a very comfortable place to be. For sure, they are not places run by independent, initiative-loving, well-motivated professionals.

This is also what you keep reading in the analyses: the Russian army functions so poorly in part because the military at the front does not dare to take initiative, which is rather disastrous in rapidly changing situations, such as a battlefield.

As can be read above (excerpt from this New York Times article), the legacy of Russian organisational culture is also still felt in the Ukrainian military.

Putin the Glorious

In Russia, everything is about power over others. Power gives social status. Wealth is just a symbol of that power. This works different Westerners. In the West, wealth directly gives social status. Moreover, because of his economic power, the Homo Economicus has limited access to political, cultural and legal power. At least, that is the ideal. Indeed, the Homo Economicus wants to be able to rely on the objective institutions of the state - those that guarantee physical safety, legal security and law enforcement. In the absence of these guarantees, the law of the jungle applies and your wealth easily confiscated. This is the situation in Russia - your wealth depends on your position in the patronage system.

In the West it is problematic when economic power gives access to cultural, political and legal power. Rupert Murdoch' s populist media empire is a case in point. In Anglo-Saxon countries, Murdoch has great influence over both politics and culture. What he does not understand is that he is taking a great risk with this. For by undermining the institutional nature of society, he too becomes vulnerable. The Homo Nobilis he puts in power, say Trump, could erode the rule of law and then take away his power and wealth with impunity.

In Russia, power is still associated with physical strength - meaning someone's ability to compromise your physical safety. This translates into all sorts of martial norms and values, the large entourages of bodyguards with which oligarchs surround themselves, and it translates into a cultural contempt for the Homo Economicus. The Homo Economicus is portrayed as a decadent, comfort- and wealth-seeking man, denying his God-given (or destiny-given) primal power.

This partly answers the question of why Putin does not care about the economic well-being of the Russian people. Not only is a self-aware middle class not in the interests of the oligarchy - after all, they could claim legal security and democracy - he just doesn't give a damn about economic well-being. He looks down on it, on all those flabby bourgeois pussies. Putin is a Homo Nobilis. He doesn't care about property, he cares about physical attributes and power.

Every self-respecting oligarch has a superyacht. These yachts are not so much utilitarian objects or investments. Rather, they are monumental objects that exude personal glory. The idea is that these objects make you feel small and insignificant, make you realise that their power is limitless. They have the same function as Pharaonic pyramids or other imperial monuments.

This focus on personal characteristics also explain his obsession with LGBTQ+ emancipation in the West. Some analysts have already christened the war "Putin's Anti-Gay War on Ukraine. In his Feb. 24 speech announcing the invasion, he argued that the West wants to impose "degenerate norms on Russia and its neighbours that are contrary to human nature”. His speeches and essays are often dismissed as rhetoric, but they fit into the worldview of the Homo Nobilis - a worldview supported by both Putin and the Russian people.

What Putin seeks is power and the manifestation of that power. He seeks glory. For himself and for Russia - a distinction that is no doubt beginning to blur in his mind. Like Louis XIV, the Sun King, who also spent his entire life waging war against the advancing Homo Economicus, Putin undoubtedly identifies the Russian State with himself. Or as Louis could so beautifully put it L'État, c'est moi - "the state, that is me. And given the personal nature of power in Russia, this is not even far from the truth.

Putin's effigy is interwoven with the world of Warhammer 40,000 in memes, among other things. A fictional world in a distant future where war is eternal and only glory, faith and violence matter. For example, the Warhammer trailer opens with "the weak and the faithless find no deliverance" and shows an ideology that fits amazingly well with Putin & Co.'s worldview.

But it is not limited to meme's. A few years ago, just outside Moscow, the Cathedral for the Armed Forces was completed. An incredible feat of worldbuilding that intertwines the ideology and symbolism of war, patriotism and Orthodox Christianity. Forged from the steel of World War II tanks, Orthodox icons, larded with stained glass Soviet medals and large tableaux of historic battles. Read more about it at The Guardian.

Putin's main goal is to impose his will on Ukraine and thereby restore Russia's (and thus his personal) status as a world power. But geopolitical reasons may not even be the main motive of his war with Ukraine. For in Putin's Russia, everything is also personal. He and his small circle of KGB oligarchs feel personally humiliated by the fall of Viktor Yanukovych, during the Maidan Revolution in 02014.

Yanukovych was a typical Homo Nobilis who served as president of Ukraine from 02010 to 2014. Already since 02002, he had a major role in national politics. He ruled a corrupt government in which he and his family members enriched themselves and in which he allowed his political opponents to be persecuted. He was thus a natural ally (read: vassal) of Putin, under whose protection he increasingly came to be since 02004.

When in 02013, under Russian pressure and against the will of the Ukrainian parliament, Yanukovych turned away at the last minute from further rapprochement with the EU and spoke out in favour of an association with Russia, he was chased out of the country after fierce riots. Following this, Russia annexed Crimea that same year and created the People's Republic of Donetsk in the east of the country.

This map explains why Putin is now focused on the conquest of eastern Ukraine. Indeed, this is the result of Ukraine's 2012 parliamentary elections. The blue districts, where Russian is widely spoken, voted for Viktor Yanukovych. The pink districts voted for Yulia Tymoshenko 's Batkivshchyna party, which seeks further integration with the EU and NATO.

Because Putin sees the territory of the former Soviet Union as Russia's natural sphere of influence and thus, by extension, as his personal fiefdom, the ousting of Yanukovych and Ukraine's rapprochement toward the EU and NATO was an unacceptable tarnishing of Russia and his personal honour and glory. For Ukraine to be seduced by the weakling world of Homo Economicus is not only morally reprehensible, it was a direct curtailment of his power, which for a Homo Nobilis can be a personal declaration of war. If he would have let this go, is would not only have cost him precious prestige among his oligarchs, but he could probably not even look at himself in the mirror.

Power is not institutional but personal for Putin. This is why the West constantly misjudged him. The West sees the world through the glasses of the Homo Economicus, or even the Homo Romanticus, but Putin looks at the world through the eyes of the Homo Nobilis. And the Homo Nobilis sees himself as a divinely inspired being who wants nothing more than to manifest himself - even if he goes down fighting in the process.

That said, it also explains why Putin doesn't care about human lives. In Putin's worldview, the value of human life is not measured in earthly terms, as in the humanistic worldview of the Homo Economicus, but in a larger mystical perspective. A perspective in which power is intrinsically subjective and arises from one's divine will. As a result, power legitimises itself. The right of the strongest is how God (or fate) wills it. It can be seen in nature, and nature is a subjective manifestation of God.

That his soldiers are dying in droves; that the Ukrainian people are suffering because of his choices; is therefore God's will. He feels no pity and so pity, as a logical consequence, is also out of place. This, of course, is incomprehensible to us in the West. Therefore, it is important to zoom out and see our own culture’s position in the Long Now. For our culture, historically at least, is not the measure of things. (Which is not to say that we are not glad we were born here and not in Putin's Russia.)

The usefulness of Historic-Futuristic lenses

As mentioned, cultural archetypes are merely lenses. They are not meant to be historical truths but tools for understanding a particular time or context. We hope this notion has provided you with a new way of looking at Putin and Putin's Russia.

We look forward to your reactions and thoughts.

Edwin and Christiaan

Hi guys! I found your point on care very much resonating to my research https://nias.knaw.nl/fellow/peter-safronov/ Be happy to get in touch with you via LinkedIn (where you could some of my works) or via email.